Killer Fungus

Fungi are everywhere, and a few species can cause very serious lethal infections. Fungal infections (mycoses) kill more people around the world than malaria. There are no vaccines to protect against fungal infections and we often diagnose them too late to save the patient.

Our exhibit at the Royal Society Summer Science Exhibition spotlights UK research that will help to improve prevention, diagnosis and treatment of mycoses.

Mushrooms aren’t always fun, guys. They can be deadly – and so can yeasts and moulds. Join us as we spotlight just how deadly fungal infections can be. You can also take part in “Outbreak!”, an app-based, problem-solving, role-playing game, in which players will battle a fungal pandemic.

You’ll have the opportunity to get up close and personal: play fungal infection computer games, explore fungal disease with 3D printed fungi and a human manikin, join in arts and crafts activities and view a time-lapse video of fungal infection spreading. Get to know the real Fungus the Bogeyman.

Outbreak!

A fungus epidemic scenario is simulated in a novel interactive experience. In this role-playing, app-based challenge, participants can work together to stop the spread.

Collaborating in groups, you will search our collection for hints, refer to scientific sources, and try to formulate a containment plan. The activity requires a smartphone and headphones for the full experience. Places can be booked on the day at the venue.

Research Stories

1.Candidalysin: a newly discovered fungal toxin

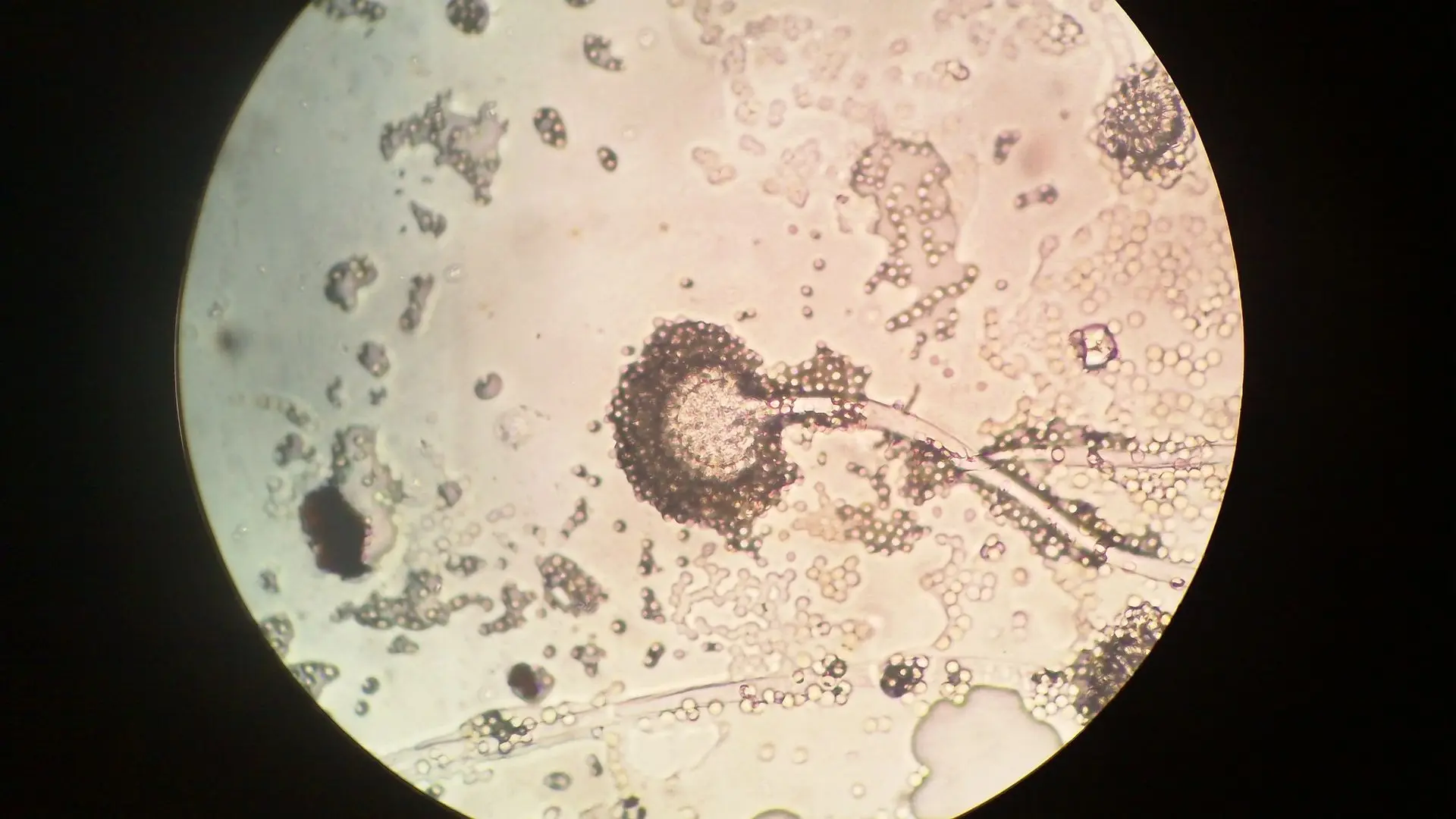

This project focuses on Candida species, which are associated with a significant global incidence of infections. A key discovery from recent research is a cytolytic peptide, Candidalysin, produced by this fungus.

biosynthesis of Candidalysin is linked to the morphological switch to the hyphal form, a phenotype associated with tissue invasion and penetration.

Experimental data further indicate that Candidalysin is a direct effector of host cell damage and the provocation of a pro-inflammatory response, although the precise molecular mechanisms remain uncharacterized.

The primary objective of this work is to characterize the specific molecular interactions between Candidalysin and host cellular components. To comprehend the toxin's involvement in pathogenicity, it is essential to clarify its method of action.

Finding these host-pathogen interactions offers a framework for looking into cutting-edge intervention techniques. With significance for the study of microbial pathogenesis, this research attempts to increase basic understanding of fungal virulence pathways.

2.Dealing with diversity – immune responses to fungi

Fungi are commonplace creatures that can be found both in the environment and in close proximity to human hosts. Most of the time, the host's defense mechanisms successfully regulate the growth of fungi.

However, fungi can cause serious infections that pose significant therapeutic hurdles in those with weakened immune systems.

An essential part of the innate immune response against fungus are phagocytic cells. With the ability to identify, absorb, and eliminate invasive microbes, these cells serve a surveillance role and are among the first to respond to a microbial breach.

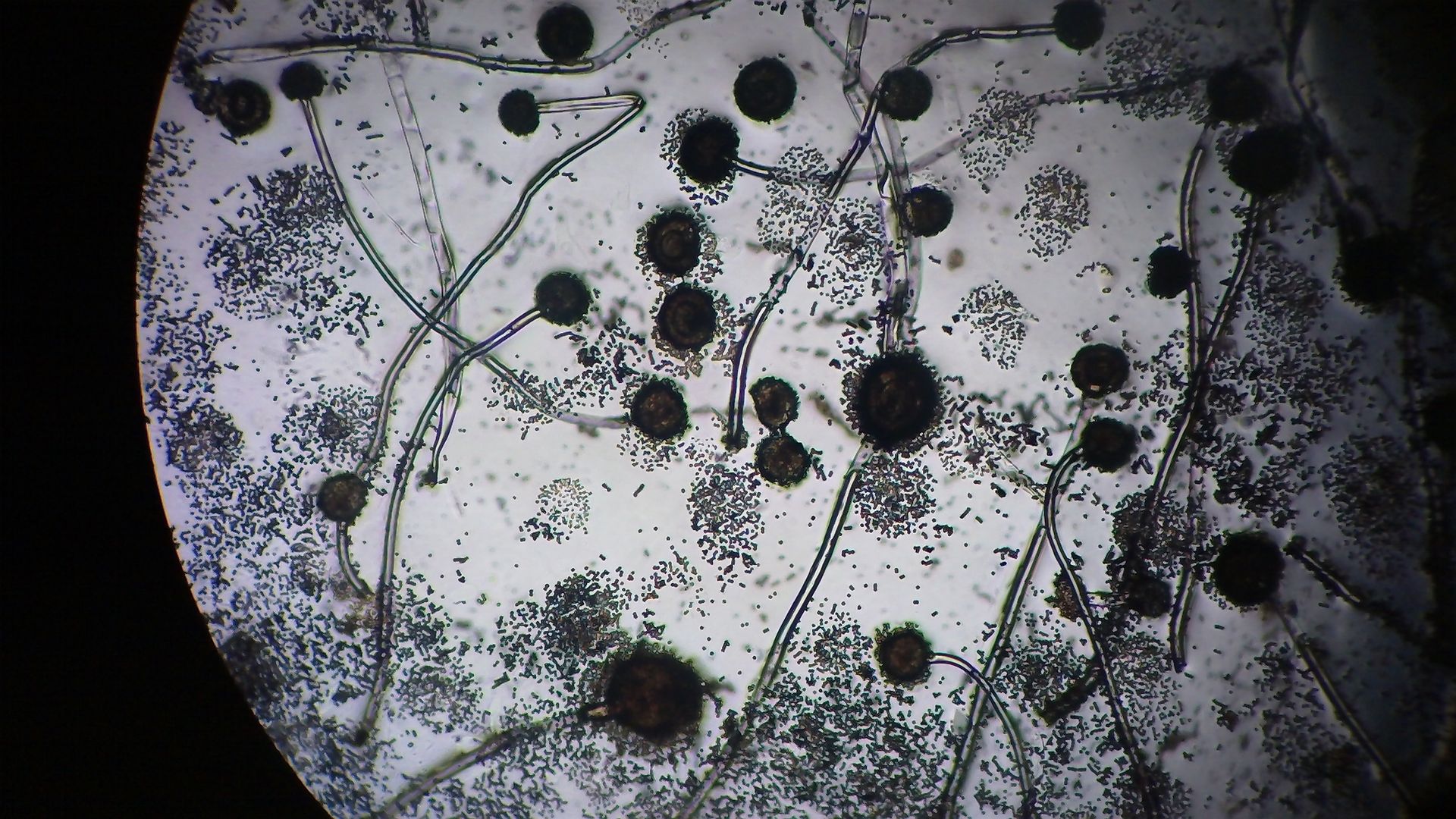

On the other hand, fungal species show a great deal of diversity. Characterizing how phagocytes interact with and react to this range of fungal targets is the aim of my doctoral research. According to preliminary research, phagocytosis kinetics vary significantly amongst fungal species.

The rate of engulfment appears to be influenced by factors including the surface composition of the fungal cell, its viability, and the presence of host-derived opsonin proteins that facilitate recognition.

A detailed understanding of the fundamental biology governing these host-pathogen interactions is a prerequisite for the future development of novel therapeutic approaches.

3.The role of mitochondria in fungal pathogenesis

A common fungal infection with clinical significance is Candida albicans, especially in patient populations with impaired immune systems. The function of mitochondria in Candida albicans cellular physiology is being studied by our research team.

Similar to eukaryotic cells, this fungal pathogen's mitochondria are vital organelles that provide energy through aerobic respiration, which is necessary for cellular growth. Moreover, important virulence characteristics, such as the content and structure of the fungal cell wall, have been linked to mitochondrial activity.

By elucidating the mechanisms through which mitochondria regulate these phenotypic factors, we aim to identify novel targets for therapeutic intervention. This knowledge may enable the development of new antifungal agents or inform the use of existing antifungals in novel synergistic combinations to enhance treatment efficacy.

4.Human lung cells: a defence against fungal spores

Every day we inhale hundreds of fungal spores but these in healthy individuals are efficiently eliminated by specialist immune cells called phagocytes which engulf and kill them. However, some human illnesses interfere with this defence mechanism, increasing susceptibility to fungal diseases.

A specialist lung tissue called the epithelium is the first line of contact between the inhaled spores and us, the host. We are working to understand how the lung epithelium interacts with the spores of a common mould called Aspergillus fumigatus.

We have generated fluorescent Aspergillus and combined this with fungal and host specific dyes to directly visulaise this interaction. We have discovered that epithelial cells ingest fungal spores and kill them.

This might provide a critical defence mechanism which is acting while we breathe, and before even phagocytes arrive at the site of the infection.

We are now trying to work out how epithelial cells grab and ingest fungal spores, by using fluorescent fungal mutants and targeted elimination of host proteins.

Once we understand this process in detail we can design new therapies to assist a quicker elimination of the dangerous fungal spores we all inhale on a daily basis

5.The heat is on; cooling down the response to Aspergillus

This research investigates the pathobiology of Aspergillus, a ubiquitous environmental fungus. Inhalation of its spores is a daily occurrence, and while typically asymptomatic in immunocompetent individuals, it can lead to significant complications in the context of specific immune dysfunctions.

A patient cohort with heightened susceptibility to aspergillosis includes individuals diagnosed with chronic granulomatous disease (CGD), a rare genetic immunodeficiency. In the CGD host, Aspergillus infections are associated with a high rate of mortality, despite the administration of standard antifungal therapies.

Our data indicate that the pathology in CGD may not be solely due to an insufficient immune response. Instead, evidence suggests a dysregulated and hyperactive immune reaction to Aspergillus, resulting in substantial immunopathology and tissue damage without effective fungal clearance.

Consequently, our research is exploring adjunctive therapeutic strategies. We are investigating whether combining conventional antifungal agents with novel immunomodulatory treatments designed to mitigate excessive inflammation can improve clinical outcomes in this specific patient population.

6.Our microscopic army against fungal killers

Cryptococcus, like many fungi, produces spores that are found in the air that we breathe. These spores will be inhaled into our lungs but they do not cause any harm because of our immune defences. However, they can cause life-threatening infections in individuals that have a weakened immune system, for example those that have AIDS or have had an organ transplant.

So, we're interested in immune cells called macrophages which are needed for immune defence against Cryptococcus.

It is impossible to see how immune cells destroy this fungus during infection because we do not have see-through bodies. So, in order to study this we are using zebrafish. Zebrafish have a similar immune system like our own but are transparent which makes it possible to see how infections happen. Using zebrafish we are testing new ways to enhance immune defences against Cryptococcus.

Ultimately these investigations may lead to development of novel therapies towards Cryptococcal infections.

7.How yeasts survive stress in the human body

This research focuses on the yeast Candida glabrata, a model organism for studying microbial persistence in host-like conditions. The investigation specifically examines the mechanisms this yeast employs to withstand environmental stressors. A key model of such stress involves interaction with phagocytic immune cells, which internalize microorganisms and expose them to an oxidative and antimicrobial compartment.

Candida glabrata demonstrates a capacity to survive and replicate within this intracellular environment. To elucidate the molecular basis of this tolerance, a series of mutants was generated and screened under simulated stress conditions.

Comparative analysis identified mutant strains exhibiting enhanced resistance phenotypes. Genomic sequencing of these mutants enabled the identification of candidate genes implicated in these defense mechanisms.

The identification of these genes provides molecular targets for further functional studies. The fundamental objective is to characterize these biological pathways, which could, in the long term, inform the development of strategies to disrupt fungal persistence.

8.The host-pathogen struggle for nutrients

An infection can be characterized as a host-pathogen interaction. During this interaction, microbial pathogens sequester essential nutrients from the host environment.

In response, a host organism can employ mechanisms to restrict the availability of essential nutrients, particularly trace metals, to inhibit microbial proliferation. This process is defined as nutritional immunity.

To persist within a restrictive host environment, microorganisms such as fungi must possess adaptive systems to cope with nutrient scarcity.

This research focuses on the adaptation mechanisms of the fungus Candida albicans to zinc limitation. Preliminary findings indicate that zinc deprivation triggers a significant alteration in the cellular morphology of C. albicans.

The objective of this investigation is to characterize the molecular regulatory pathways that govern this morphogenetic switch and to evaluate its impact on microbial persistence and fitness within a model system. The fundamental aim is to advance the understanding of microbial adaptation to nutrient stress.